HP3 Ankle Sprain Return To Sport Check

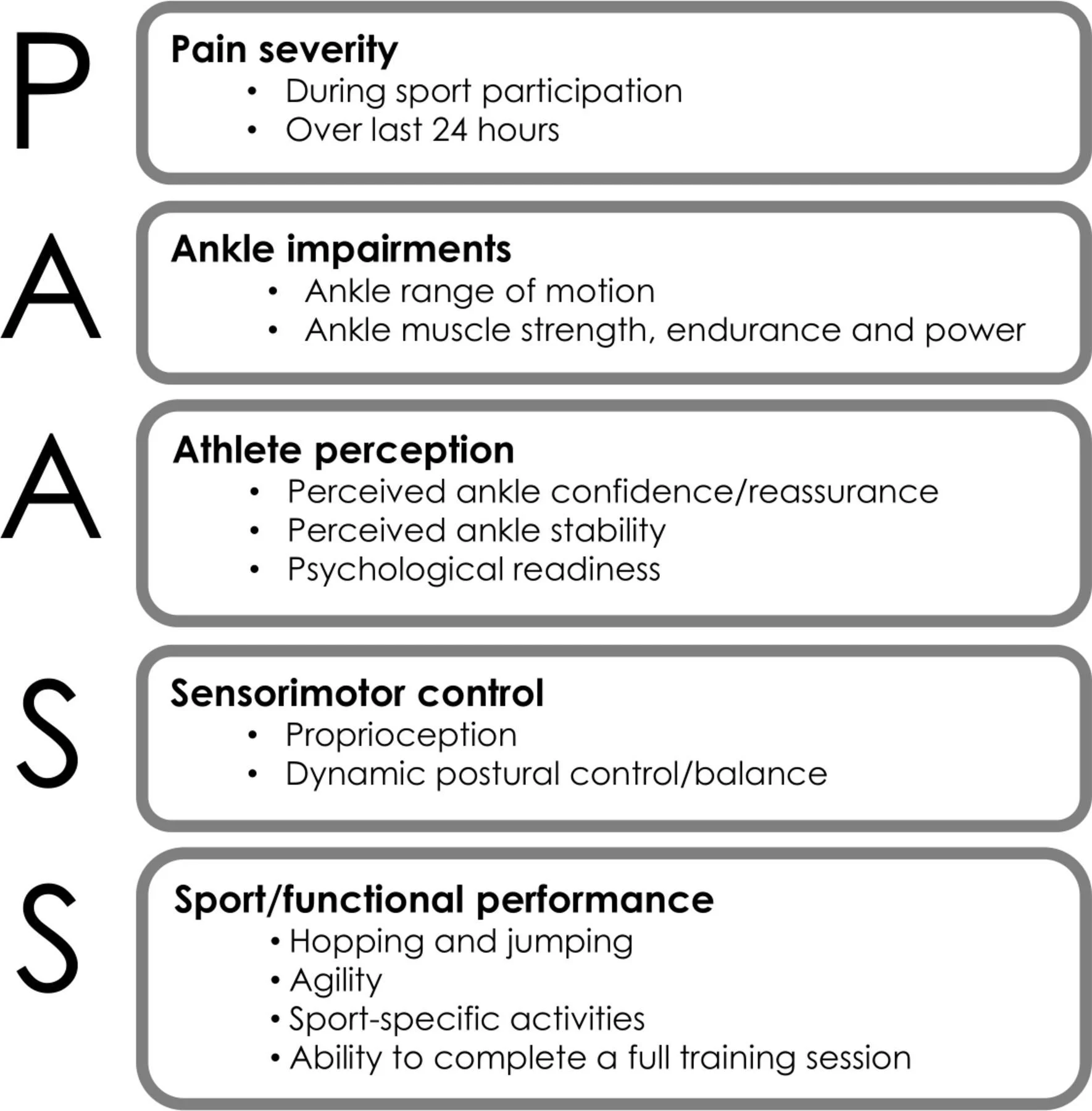

This ankle self-check has been built from current research on return to sport after lateral ankle sprain. It combines the PAASS framework, which was developed by an international expert group to define what should be considered before return to sport, with elements of the Ankle-GO score and recent research on balance, hopping and confidence that predicts who is more likely to struggle or re-injure their ankles.

Lateral ankle sprains are often treated as “minor”, but a substantial proportion of people do not fully recover (Flore et al. 2024). Large cohort and review data suggest that around 20–40 % of patients go on to develop chronic ankle instability, particularly when sprains are under-rehabilitated, and that previous sprain is one of the strongest predictors of future problems (Raeder et al. 2021). Research on structured return-to-sport testing shows why it is not enough simply to “wait a couple of weeks” and then go back to play. The PAASS consensus highlights that pain alone is insufficient; clinicians should also review ankle impairments (swelling, range, strength), athlete perception (confidence and fear), sensorimotor control (balance and “giving way”), and sport-specific performance before clearing an athlete. The Ankle-GO studies go further, showing that athletes who meet a higher multi-domain score at around two months have a much lower risk of re-sprain, whereas those with low scores have roughly a nine-fold higher risk of recurrence over the following two years (Picot et al. 2024). More recent work suggests that problems with visual and cognitive processing under pressure may also matter, which is why this check includes tasks that challenge balance and control rather than just asking about pain.

This self-check is designed to translate those research principles into plain language so that you, your coach and your clinician can review the same key domains together. By taking a few minutes to reflect on pain, function, confidence, balance and sport-specific tasks before you push back to full training or competition, you are reducing the likelihood of an early, risky return that sets you up for repeat sprains and chronic ankle instability, and increasing the chance that your rehab time actually “buys” you long-term robustness.

Your answers are used to create a simple “traffic light” result for each of these areas and for your overall pattern:

Green means your responses are closer to what we would expect in a low-risk profile, although it is not a clearance to return.

Amber means there are one or more areas that still look vulnerable, so progressing cautiously and addressing those areas is sensible.

Red means your pattern is more consistent with higher ongoing risk, especially if you report recent “giving way”, difficulty hopping or major loss of confidence.

You can use the result in several ways. It can help you decide whether you are likely to benefit from a structured rehabilitation plan rather than just “rest and hope”. It can give you a clearer starting point to discuss with a physiotherapist, sports doctor or coach, and you can repeat the check every few weeks to see whether your risk pattern is changing as you work through rehab. If your result is amber or red, or if you are unsure what to do next, we recommend booking a proper assessment so that your return to sport is guided by a full clinical examination rather than this screening tool alone.

HP3 ankle return-to-sport self-check

This tool helps you reflect on key areas that influence ankle sprain recovery: pain, movement, confidence, balance, sport performance, and injury history. It runs in your browser only and does not store your answers.

If any of the following apply to you now, you should seek urgent medical advice rather than using this self-check:

If any of these are ticked, this tool will still calculate a risk pattern but will highlight that you need a medical assessment first.

Important information and disclaimer

This ankle return-to-sport self-check is provided by HP3 for general information and education only. It does not provide a diagnosis, does not constitute medical advice, and does not replace an individual consultation with a qualified healthcare professional who can assess you in person. Using this tool does not create a clinician–patient relationship with HP3 or any of its staff. You remain responsible for your own health decisions and for seeking appropriate medical assessment, particularly if you have severe pain, marked swelling, deformity, difficulty weight-bearing, systemic symptoms, or any other concern about your injury. HP3, its clinicians and coaches accept no responsibility or liability for any loss, injury or damage suffered by any person as a result of using, or relying on, this tool or the information it generates, except where such liability cannot be excluded or limited under applicable law.

References

Flore Z, Hambly K, De Coninck K, Welsch G. A Rehabilitation Algorithm After Lateral Ankle Sprains in Professional Football (Soccer): An Approach Based on Clinical Practice Guidelines. IJSPT. 2024;19(7):910-922

Picot, B., Fourchet, F., Lopes, R. et al. Low Ankle-GO Score While Returning to Sport After Lateral Ankle Sprain Leads to a 9-fold Increased Risk of Recurrence: A Two-year Prospective Cohort Study. Sports Med - Open 10, 23 (2024).

Raeder, C., Tennler, J., Praetorius, A. et al. Delayed functional therapy after acute lateral ankle sprain increases subjective ankle instability – the later, the worse: a retrospective analysis. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 13, 86 (2021).

Smith MD, Vicenzino B, Bahr R, et al Return to sport decisions after an acute lateral ankle sprain injury: introducing the PAASS framework—an international multidisciplinary consensus British Journal of Sports Medicine 2021;55:1270-1276.